Foreword

What do we mean by agroecology? What does it look like? Is it scalable? Can we give concrete examples? How could we invest in or support it? Is it productive? Is there data proving its efficiency; that it is delivering on its promises? These are a few of the questions that often come up when speaking with people who are not terribly familiar with agroecology. When talking with people who are familiar with it, they raise other issues:

“I don’t think they are really talking about agroecology: agroecology is not restricted to improving life in soils, it is so much more than that!”

“It’s incredible, they use the word agroecology, but they’ve totally emptied it of its true meaning, it looks like they are using it to green-wash the industrial model”

“This might be how scientists are interpreting agroecology but peasant movements see it differently”

”He/she’s not using the concept of agroecology but what he/she’s talking about is very much in line with how we see and define agroecology”

We could go on and on. Generally speaking there is a need to clarify what agroecology is and what it is not in order to gather political support, for the discipline to flourish, to avoid co-optation and fight against false solutions etc. Social movements, civil society, international institutions, and academics have made several attempts to clarify what agroecology means over recent years and this trend continues with many still trying to clarify it.

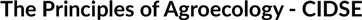

In our network, we felt there was a similar need for clarification and alignment. What follows is the initial outcome of this work. We decided to split the different principles into the four dimensions of sustainability: environmental, socio-cultural, economic and political. We believe it is a good way to capture the complexity and multi-dimensional aspect of agroecology. It allows us to understand agroecosystems and food systems by taking into account the social, economic, and political contexts in which they sit.[1] It also builds on categories of principles that have already been identified in previous work done by others in the agroecological movement.

We are clear what we are trying to achieve. Our aim is not to build a new definition of agroecology but rather to identify principles that will strengthen our narrative as well as our advocacy and programme work. We want to develop further a common vision and understanding of what agroecology (which we see as one of the main elements in achieving food sovereignty and climate justice) means and looks like.

This is the first step in a broader process that will also include the development of a practical guide which, together with these principles, should serve as the basis for initiating a dialogue in different parts of the world and within the member organisations of our network (assessing current practices and strategies). As our societies face deep social, environmental and economic crises and climate change imposes on our societies deep and radical shifts from current models of production and consumption, there is a certain urgency for agroecology to be understood and supported widely. With this humble contribution, we hope and believe that we can contribute to strengthening the existing agroecological movement, which is the purpose of what we are doing on agroecology.

Prof. Michel Pimbert, Coventry University (UK)

Diving into Agroecology: background information

The three facets of agroecology

Agroecology is:

1. A scientific research approach involving the holistic study of agro-ecosystems and food systems,

2. A set of principles and practices that enhances the resilience and sustainability of food and farming systems while preserving social integrity,

3. A socio-political movement, which focuses on the practical application of agroecology, seeks new ways of considering agriculture, processing, distribution and consumption of food, and its relationships with society and nature.

The interdependence of agroecology and food sovereignty

“There is no food sovereignty without agroecology. And certainly, agroecology will not last without a food sovereignty policy that backs it up”. Ibrahima Coulibaly

We wish to build on the perspectives developed by social movements actively involved in shaping and defining food systems. We also recognize and respect the work that has been done so far to clarify and develop the concept of agroecology and consider it as laying the foundations of this work.

The Nyéléni Declaration defines agroecology as a people-led movement and practice that needs to be supported, rather than led, by science and policy. We understand this as an urgent call for the expertise of food producers and those working in community food to be recognized and put at the centre of policymaking and food systems governance. It also calls for the right of people “to control food policy and practice”. From this perspective, agroecology is, indeed, inseparable from food sovereignty.

Principles: definition and characteristics

Principles are a set of broad guidelines that constitute the building blocks of agroecology, its practice and implementation. They build on the following characteristics:

- Agroecology promotes principles rather than rules or recipes of a transition process,

- Agroecology is the result of the joint application of its principles and their underlying values to the design of alternative farming and food systems. It is therefore acknowledged that the application of the principles will be done progressively,

- The principles apply across locations and lead to different practices being used in different places and contexts,

- All principles should be interpreted in the context of improving integration with the natural world, and justice and dignity for humans, non-humans and processes.

CIDSE views on food sovereignty: “Food sovereignty is a policy framework which addresses the root problems of hunger and poverty by refocusing the control of food production and consumption within democratic processes rooted in localised food systems. It embraces not only the control of production and markets, but also people’s access to and control over land, water and genetic resources. It assumes the recognition and empowerment of people and communities to realise their economic, social, cultural, and political rights and needs regarding food choices, access and production. It is defined as: “The right of peoples to define their own food and agriculture; to protect and regulate domestic agricultural production and trade in order to achieve sustainable development objectives; to determine the extent to which they want to be self reliant; to restrict the dumping of products in their markets. Food sovereignty does not negate trade, but rather it promotes the formulation of trade policies and practices that serve the rights of peoples to food and to safe, healthy and ecologically sustainable production”. “Food Sovereignty: Towards democracy in localised food systems” by Michael Windfuhr and Jennie Jonsén, FIAN-International (2005). CIDSE, EAA (2013). “Whose Alliance? The G8 and the Emergence of a Global Corporate Regime for Agriculture, CIDSE and EAA Recommendations”, p.7.

Visualizing Agreocology

An infographic summarizing the Agroecology Principles

You can download the infographic in high quality here.

1. Environmental Dimension of Agroecology

1.1 Agroecology enhances positive interaction, synergy, integration, and complementarities between the elements of agro-ecosystems (plants, animals, trees, soil, water, etc.) and food systems (water, renewable energy, and the connections of re-localised food chains).

1.2 Agroecology, builds and conserves life in the soil to provide favourable conditions for plant growth.

1.3 Agroecology optimises and closes resource loops (nutrients, biomass) by recycling existing nutrients and biomass in farming and food systems.

1.4 Agroecology optimises and maintains biodiversity above and below ground (a wide range of species and varieties, genetic resources, locally-adapted varieties/breeds etc) over time and space (at plot, farm and landscape level).

1.5 Agroecology eliminates the use of and dependency on external synthetic inputs by enabling farmers to control pests, weeds and improve fertility through ecological management.

1.6 Agroecology supports climate adaptation and resilience while contributing to greenhouse gas emission mitigation (reduction and sequestration) through lower use of fossil fuels and higher carbon sequestration in soils.

Impact of this dimension:

Through is environmental dimension and by applying principles which tend to mimic natural ecosystems, agroecology contributes to building more complex agroecosystems. Agroecology increases resilience and the capacity for systems to adapt to climate change in contexts in which climatic risks are common. For instance, “it has been demonstrated that increased biodiversity in the soil improves water use, nutrient uptake, and disease resistance of crop plants”. By delivering resilience, biodiversity often acts as a “buffer against environmental and economic crisis”. Through its environmental dimension, agroecology therefore helps to build self-sufficient, healthy, pollution-free systems that provide an accessible and diverse range of safe food, energy and other domestic needs. As a co-benefit of the application of its principles, agroecology also contributes to mitigating climate change e.g. building healthy soils and restoring depleted soils – thus contributing to carbon sequestration – or by reducing direct and indirect energy use – thus avoiding greenhouse gas emissions. Through efficient use of resources (such as water, energy use, etc.), agroecology also contributes to building resilience and increasing its efficiency. Beyond this major potential for resilience, mitigation and adaptation, agroecology provides a healthy, safe working environment for farmers and farm labourers as well as a healthy environment for rural, peri-urban and urban communities while providing them with healthy, nutritious, diversified food.

Michel Pimbert, Professor at Coventry University, UK

Example 1: Resilience, extreme weather events, and agroecology

Several studies looking at agricultural performance after extreme weather events (droughts and hurricanes) in Central-America have shown that “resilience to climate disasters is closely linked to farms with increased levels of biodiversity” and ”when inserted in a complex landscape matrix, featuring adapted local germplasm deployed in diversified cropping systems managed with organic matter-rich soils and water conservation-harvesting techniques”. For instance “a survey conducted … in Central America after Hurricane Mitch showed that farmers using diversification practices (such as cover crops, intercropping and agroforestry) suffered less damage than their conventional monoculture neighbours”. Similarly, “forty days after Hurricane Ike hit Cuba in 2008, researchers found that diversified farms exhibited losses of 50%, compared to 90 or 100% in neighbouring monocultures” while “agroecologically managed farms showed a faster productive recovery (80 –90%) 40 days after the hurricane than monoculture farms.”

Sources/further information

– Machín Sosa, B., Roque Jaime, A. M., Ávila Lozano, D. R., Rosset Michael, P. (2013). Agroecological revolution: The Farmer-to-Farmer Movement of the ANAP in Cuba.

– Holt-Giménez, E. (2002). Measuring Farmers’ agroecological resistance to hurricane Mitch in Central America.

Altieri, M. & Nicholls, C. & Henao, A. & Lana, M. (2015). Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems.

Example 2: Transforming Soil and Livelihoods in Rural Bangladesh

Since the late 1970s, chemical fertilisers and pesticides, though more expensive than organic alternatives, have increasingly been pushed on to farmers across Bangladesh as part of the Green Revolution approach, resulting in harmful implications for human health, soil and water quality. The subsidising of chemical fertilisers and the pressure placed on farmers to produce sufficient yields to meet Bangladesh’s rapid population growth, has led to an over-dependence on and indiscriminate application of chemical fertilisers and pesticides over organic matter. Failure to replenish soil with organic matter has left soils in many parts of Bangladesh lacking sufficient nutrients for agricultural productivity.

Depleting organic matter reserves in soils has also had implications for food security in Bangladesh in the face of rising climate change vulnerability. Unpredictable rains and unexpected weather conditions are making it increasingly difficult for farmers to plan their production effectively, with depleting soil health exacerbating the issue further. Improving Bangladesh’s soil fertility is, therefore, crucial for smallholder farmers to better withstand and adapt to the impact of climate change, enabling them to provide food for their families and wider communities, strengthen local markets and develop thriving, sustainable livelihoods for generations to come.

CAFOD has partnered with Caritas Bangladesh, USS Jessore, Practical Action Bangladesh and Caritas Switzerland to put agroecological principles at the heart of a three-year DFID-funded Climate Resilient Agriculture project, working with smallholder farmer communities in the Dinajpur, Rajshahi, Jessore and Sylhet divisions of Bangladesh.

A key component of the project has included introducing farmers to the production and use of vermicompost – a nutrient rich, organic fertiliser produced from the excreta of earthworms – which can be easily prepared using materials already found within farming systems including cow dung, banana leaf and kitchen waste. After participating in training sessions on the preparation of vermicompost and visiting demonstration plots, farmers involved in the project began to produce their own vermicompost and applied it to their soil. The results have been quite remarkable.

Farmers across all project areas have witnessed an improvement in the fertility of their soil through an increase in the quantity and quality of their crops after using vermicompost. They have also observed a reduction in harmful pests and diseases which would usually adversely affect their production. Key findings from the project include: over 8,600 project households have increased their food production by at least 20% after using vermicompost on their soil. 6,327 project households have been able to produce multiple crops (from 3-12 different vegetable varieties) on previously unproductive land after using vermicompost alongside the bedding approach in their farming. In addition, 7,067 households have reported that they have generated additional income as a result of the project, largely attributable to the sale of surplus crops produced using vermicompost. These findings are corroborated by research completed by CAFOD’s partner Practical Action and IIED [International Institute for Environment and Development] in 2016, which calls for greater promotion of agroecological practices (including vermicompost) by upscaling the use of organic matter to improve soil fertility and crop production.

Razia Begum, from Jessore, recorded a 150% increase in her production of bitter gourd after using vermicompost and herbal pesticides, while significantly reducing the application of chemical fertiliser on her soil. As a result, Razia has not only been able to provide sufficient food for her family but has been able to sell her surplus produce and vermicompost for additional income. She has also been able to generate income from her expertise in vermi-compost production through facilitating training sessions with farmer field schools in her locality. Her husband, who previously discouraged her involvement in activities that took her away from domestic work, is now keen to support Razia’s entrepreneurial initiative. Like Razia, Jamal Hossain, from Lebutola Union, has observed improvements in the quantity, appearance, longevity and taste of his crops when using vermicompost and herbal pesticides compared to chemical fertiliser: “I really believe in this farming method and I now have evidence to show my neighbours that it works! Vermi-compost is not just good for my crops and my income but it’s good for the environment and our health. We need to encourage the next generation to move away from chemical to organic farming – it is better in so many ways”.

In addition to enhancing crop yields, thus improving food security, this project has contributed to the rehabilitation of soil health, decreased incidence of pest and disease outbreaks, increased incomes for farmers and promoted greater entrepreneurial opportunities for women in farming communities. This project demonstrates the economic and environmental principles of agroecology in practice and promotes sustainable agriculture that works for people and the planet.

Sources/further information

For more information on how agroecological farming practices can contribute towards improved soil fertility in Bangladesh, please see Practical Action and IIED’s action research paper, entitled, “Collaborative Action on Soil Fertility in South Asia”.

Example 3: Increasing resilience through mangrove rice cultivation

Mangrove rice cultivation is a resilient system practiced in Western Africa since the fifteenth century. It is land “stolen” from the sea through the labour-intensive construction of a belt of dams and careful water management (rain and seawater) to control the salinity and acidity of the soil. Cultivation used salt- and drought-tolerant rice varieties that came from heterogeneous seed sources mainly introduced, spread and multiplied over the years by farmers themselves. Mangrove rice farming avoids the use of chemical fertiliser as well as herbicide and fungicides.

In the context of Guinea Bissau, a country with a very high per capita rice consumption (110-120 kg/pp/year) and high dependency on imports, the dismantling of Guinea’s peasant world and the impoverishment of native rice varieties are undermining the productive and cultural socio-ecological system of mangrove rice-growing practiced mainly by the Balanta ethnic group. Therefore, over a decade, LVIA-FOCSIV with local key stakeholders has been developing and implementing a national resilience strategy, based on mangrove rice growing, diversified farming, a more balanced diet and shorter supply chains. The strategy has different components such as increasing awareness and knowledge of mangrove land use, more efficient communal water management and the farming system. The improved knowledge and know-how was combined with the development of irrigation facilities and a programme of applied research for local rice improvement, fostering its adaptation as well as increasing productivity in the field but also “in the pot and the belly”. The strategy was defined with and supported by rural communities (“tabanka”), cooperative societies, government stakeholders and research centres through a governance system that encouraged the growing farmer movement, strengthening social and institutional capacities to improve system resilience and the ability to address weaknesses.

So far, improvement of the hydraulic system and water management coupled with the adoption of improved agricultural techniques into a balanced agro-ecological system, has produced rice yields of 4 tons/ha without any chemical inputs (fertiliser, herbicide and fungicides). This is more than twice the average yield of non-irrigated lowland rice (1-2.5 tons/ha with agro-inputs and only 0.7-1.2 tons/ha with limited agro-inputs). The increase in land and labour productivity is an astonishing result, and translates into more income for farmers, local investment, and involvement of young people in farming and at the same time has led to proper recognition of the value of this special socio-ecological system. The increased self-esteem of Balanta farmers of Guinea-Bissau has been demonstrated by their engagement with government to safeguard the local product, demanding support in terms of investment but also the setting-up of “experience exchange, dialogue and strategic thinking to improve our work and the access of our rice to the local market” (Siaca – farmers of Kampiane Village, Guinea Bissau). The resilience strategy increased rural communities’ ability to transform their sustainable development trajectory through a greater voice in decision making in the governance structure.

This example demonstrates particularly the environmental dimension of agroecology in the positive interaction, synergy, integration and complementarities between the different elements of agro-ecosystems. It also demonstrates the economic dimension of agroecology, because, among other things, it shows that agroecology reduces dependence on aid and reinforces community autonomy by encouraging sustainable livelihoods and dignity, and promotes independence from external inputs.

Sources/further information

-Cerise, S., Mauceri, G., Rizzi, I. (2017). Mangrove Rice Cultivation in Guinea Bissau within “The Construction of communities’ resilience in African Countries – Three case studies by FOCSIV NGOs”, Collana Strumenti, FOCSIV n.49.

-Temudo, M. (2011). Planting Knowledge, Harvesting Agro-Biodiversity: a case study of Southern Guinea-Bissau rice-farming; Hum. Ecol (2011) 39: 309-321, Springer Science.

-Andreetta, A., Delgado Huertas, A., Lotti, M., Cerise, S. (2016). Land use changes affecting soil organic carbon storage along a mangrove swamp rice chronosequence in the Cacheu and Oio regions (Northern Guinea-Bissau) Agriculture, Ecosystem and Environment 216 (2016) 314-321.

Reportage (Italian)

2. Social and Cultural Dimension of Agroecology

2.1 Agroecology is rooted in the culture, identity, tradition, innovation and knowledge of local communities.

2.2 Agroecology contributes to healthy, diversified, seasonally- and culturally-appropriate diets.

2.3 Agroecology is knowledge-intensive and promotes horizontal (farmer-to-farmer) contacts for sharing of knowledge, skills, and innovations, together with alliances giving equal weight to farmer and researcher.

2.4 Agroecology creates opportunities for and promotion of solidarity and discussion between and among culturally diverse peoples (e.g. different ethnic groups that share the same values yet have different practices) and between rural and urban populations.

2.5 Agroecology respects diversity between people in terms of gender, race, sexual orientation and religion, creates opportunities for young people and women and encourages women’s leadership and gender equality.

2.6 Agroecology does not necessarily require expensive external certification as it often relies on producer-consumer relations and transactions based on trust, promoting alternatives to certification such as PGS (Participatory Guarantee System) and CSA (Community-Supported Agriculture).

2.7 Agroecology supports peoples and communities in maintaining their spiritual and material relationship with their land and environment.

Impact of this dimension

As it starts from the existing knowledge, skills and traditions of farmers and food producers, agroecology is particularly well-suited to achieving their right to food. It allows the development of appropriate technologies closely tailored to the needs and circumstances of specific small-scale farmers, peasants, indigenous people, pastoralists, fisherfolks, herders, hunter-gatherers communities in their own environment. In most developing countries, agriculture remains the most common occupation and the sector therefore offers the best opportunities for inclusive development. As such, it can help reverse rural-to-urban migration and family fragmentation. If people learn and apply agroecological practices and develop and control the value chain up to the end user, rural life and food production (in rural or urban environments) will once more be attractive and valued by society, thereby contributing to thriving local economies, social cohesion and stability.

By placing food producers at the heart of food systems (peer-to-peer exchanges of practice, promotion of food producers’ skills, etc.), increasing autonomy and revitalizing rural areas, agroecology contributes to giving a new value to peasant identities and strengthening peasant confidence and involvement in their local food system.

Lynn Davis, La Via Campesina (UK)

By bringing producers and consumers closer in shorter, more local value chains, and strengthening both groups’ role and voice, agroecology contributes to restoring justice to the food system by decoupling it from corporate power. It promotes trust and solidarity in the producer-consumer relationship and provides for nutritious, healthy and culturally-appropriate food for both groups. It supports local food diversity, thus helping protect local cultural identities. More direct marketing also reduces the food system’s carbon footprint and pollution by reducing processing, packaging and transport.

Krinshnakar Kumari, MIJARC (India)

Agroecology creates opportunities for women to increase their economic autonomy and, to some extent, influence power relationships, especially within the home while also expanding the diversity and value of roles available to men. Agroecology as a movement is supportive of women’s rights because of its inclusiveness, the fact that it recognizes and supports women’s role in agriculture, and because it encourages women’s participation. Being in essence a struggle for social justice and emancipation, the agroecological movement should always go hand-in-hand with active feminism. As the impact of agroecology on gender relations is not automatically positive, a specific focus on women while implementing agroecology in its various dimensions is required.

Example 1: Access to land and agroecology: a contribution to empowering women in India

Social change and empowering women are key elements in the agroecology process. A recent study in Maharashtra, India, based on interviews with 400 smallholder households, shows how women started sustainable and diversified food production after getting access to land. In the study area, women had very little power of decision as regards agriculture. The so-called “one acre model” encouraged women to convince their husbands to allocate them a plot of land. On this plot, women cultivated a variety of food crops (cereals, pulses and vegetables). They applied practices such as mixed cropping systems to improve crop diversity, reduced the application of chemicals by using farm yard manure, compost and organic remedies, and reduced cash crops (sugar cane, soya beans), both for nutritional security and better water management. This was important, as the region has suffered one of the severest droughts in 75 years.

The study showed that as a consequence of these positive changes in gender roles and the increased availability of food, young girls and women could eat more and more healthily. Interviewees in the study clearly indicated that the quality and freshness of their food was much better and consequently the health of the whole family had improved. The value of home-consumed food was 67% higher compared to the farmers of the reference group, who focused on cash crops. Taking account of the value of home-consumed food in households’ total gross income, it was clear that the agroecological approach revitalized farm incomes in rural households. This was particularly important in the context of drought, which pushed poorer households into deep debt.

The study also revealed that by using this approach most women gained decision-making power regarding land, cultivation and even marketing. Apart from access to land, women’s engagement in leadership courses and women groups was essential. Almost 25% of women themselves became trainers and leaders, to share with others their knowledge of agroecological farming practices, farm management and marketing.

The social and cultural dimension of agroecology is deeply concerned about roles and seeks to recognize and support fairer relationships at all levels in food systems. This example shows how agroecology, by taking gender into account and giving women their place, can contribute to empowerment.

Sources/further information

Bachmann, Lorenz, Gonçalves, André, Nandul, Phanipriya (2017). Empowering women farmers’ for promoting resilient farming systems. Sustainable pathways for better food systems in India.

3. Economic Dimension of Agroecology

3.1 Agroecology promotes fair, short distribution networks rather than linear distribution chains and builds a transparent network of relationships (often invisible in formal economy) between producers and consumers.

3.2 Agroecology primarily helps provide livelihoods for peasant families and contributes to making local markets, economies and employment more robust.

3.3 Agroecology is built on a vision of a social and solidarity economy.

3.4 Agroecology promotes diversification of on-farm incomes giving farmers greater financial independence, increases resilience by multiplying sources of production and livelihood, promoting independence from external inputs and reducing crop failure through its diversified system.

3.5 Agroecology harnesses the power of local markets by enabling food producers to sell their produce at fair prices and respond actively to local market demand.

3.6 Agroecology reduces dependence on aid and increases community autonomy by encouraging sustainable livelihoods and dignity.

Impact of this dimension

Judith Hitchman, President & co-founder of Urgenci

By using local resources and providing food to local and regional markets, agroecology has the potential to boost local economies and contribute to eliminating the negative impact of international ‘free’ trade on small-scale food producers’ livelihoods. Agroecological practices are economically viable as agroecological production methods reduce the cost of external inputs and therefore allow greater financial and technical independence and autonomy for food producers. By diversifying production and peasant activity, food producers are less exposed to market-related risks such as price volatility or loss due to extreme weather events exacerbated by climate change. Small-scale farmers in particular benefit from implementing agroecology, as they can sustainably increase their yields, improve their food and nutrition security and raise their income. With regard to productivity and revenues, agroecology is particularly beneficial for less well-off households and can thus be described as inherently “pro-poor”. Agroecology also contributes to economies by providing appropriate technology and food-based employment opportunities in rural and peri-urban areas. At the same time, it can offer a livelihood for people in cities with a small plot or access to public land. One of the objectives of agroecology is to provide decent work that respects human rights and provides a decent income for food producers. By decreasing the distance between producer and consumer, agroecology reduces storage, refrigeration and transport costs, as well as food loss and waste. Agroecology takes externalities for society and environment fully into account, as it minimizes waste and reduces effects on health, and supports positive externalities such as ecological health, resilience and regeneration.

Example 1: Agroecology benefits rural economies

In 2016, Trócaire, with local partner organisation, Red K’uchubal prepared a research call with the aim of estimating food and resilience-related changes among small-scale farmers who had adopted agro-ecological practices in Western Guatemala. The Programme for Territory and Rural Studies at the University of San Carlos in Guatemala was to the fore in the team that carried out the research in 2016 by comparing outcomes based on a range of social, economic and environmental criteria between a group of ten agroecology-adopting farmers with a group of ten semi-conventional farmers. The findings from the research were finalised in 2017 and are reflected in a report in Spanish (with short English abstract) and a video resource, also in Spanish with English subtitles.

With regard to the economic dimension of agroecology, the research found statistically significant differences in gross agricultural income. The agroecology farmers achieved higher levels of agricultural incomes than their semi-conventional peers. As a result, agro-ecological farmers said they generated enough income to live off the land throughout the year while their semi-conventional counterparts said they needed to supplement their farm incomes with off-farm employment. This outcome was due to a number of factors including:

– Achieving comparable yields in crops such as maize but without reliance on expensive inputs, including chemical fertiliser, pesticide and herbicides,

– Better locally-based market integration associated with more diverse production, and

– Lower dependency on food purchases to meet food and nutritional needs; food-related weekly expenditure in agroecological households on average representing just 47% of that in conventional households.

The video resource looks at the development of agroecological production chains and the important role of farmer co-operatives in marketing diverse agro-ecological product lines, illustrating how agroecology provides for farmer livelihoods while also contributing to strengthening local markets, local economies and employment.

Sources/further information

Praun, A., Calderón, C., Jerónimo, C., Reyna, J., Santos, I., León, R., Hogan, R., Córdova, JPP. (2017). Algunas evidencias de la perspectiva agroecológica como base para unos medios de vida resilientes en la sociedad campesina del occidente de Guatemala.

Example 2 : How a microfinance institution tailored financial products to the environmental impact of farming practices

Developing and financing the transition and adaptation to agroecological practices is an important issue for many farmers’ organizations in West Africa. The stakeholders in the PAIES programme, CCFD and SIDI (the microfinance branch of CCFD), have been tackling this issue on behalf of their partners since 2014 in putting together its PAIES programme (supporting farmers making the transition to agroecology). Transition cannot rely on direct support from the NGO alone; it also needs to be included in microfinance practices and products available to farmers.

To address issues facing all farmers’ organizations, UBTEC, a microfinance institution (Caisse d’Epargne et Crédit), studied the agroecological practices of its members to develop financial products with a bonus/penalty system (a lower/higher interest rate) linked to the environmental impact of farming practices.

This research produced a catalogue of agricultural practices in northern Burkina Faso and analysed the profitability of production linked to the methods and practices used (employing chemical inputs or agroecology). A catalogue of the most sustainable farming and non-farming practices (taking account of the ecological, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability at all times) was produced. This catalogue helped UBTEC promote sustainable practices through its current finance products.

It showed that some crops had the potential to be more profitable if farmers use an agroecological approach and methods such as using organic fertilizers, natural pesticides (onions, potatoes or cowpeas) but also that others could be less profitable, or unprofitable (tomatoes, chillies or cabbages). This is an important point. A balance needs to be found between profitability and the agroecological approach that respects the environment and health of producers and consumers. Through the research, the characteristics of agroecological practices were set out to help design a model for implementing and prioritizing them at farm level. In addition, it analyzed different types of investments farmers made to increase yields, lock-ins that food producers faced and possible strategies to minimize them. These different components of the research allowed UBTEC to propose ways of financing and selecting farming activities that could be financed, as well as practical ways of supporting borrowers adopting agroecology. In late 2017, the outcome of the study and partnership were marked by the launch of new financial products (seasonal agricultural loan) supported by a guarantee fund. In this, UBTEC started to lend money to its members with an interest rate varying according to the practices adopted and their environmental impact. Agroecology attracts a lower rate; non-agroecology, a higher rate. Within 4 months of launching the loan, there had been 450 applications from farmers to finance agroecological practices.

Sources/further information

“Rapport de l’étude pour adapter les produits financiers de l’UBTEC avec un système de Bonus/Malus en fonction de l’impact environnemental des activités financées : Programme PAIES »

Video on the research and how it was carried out.

4.Political Dimension of Agroecology

4.1 Agroecology prioritises the needs and interests of small-scale food producers who supply the majority of the world’s food and it de-emphasizes the interests of large industrial food and agricultural systems.

4.2 Agroecology puts control of seed, biodiversity, land and territories, water, knowledge and the commons into the hands of the people who are part of the food system and so achieves better-integrated resource management.

4.3 Agroecology can change power relationships by encouraging greater participation of food producers and consumers in decision-making on food systems and offers new governance structures.

4.4 Agroecology requires a set of supportive, complementary public policies, supportive policymakers and institutions, and public investment to achieve its full potential.

4.5 Agroecology encourages forms of social organisation needed for decentralised governance and local adaptive management of food and agricultural systems. It also incentivizes the self-organisation and collective management of groups and networks at different levels, from local to global (farmers organisations, consumers, research organisations, academic institutions, etc).

Impact of this dimension

Through its political dimension, agroecology transfers the source of power in food systems from focusing on the interests of an increasingly small number of large industrial agricultural entities to direct producers, ie small-scale food producers who supply the majority of the world’s food. It challenges and helps remedy the injustices caused by corporate power’s domination in the existing food system. When part of a food sovereignty approach, agroecology represents a democratic transition in food systems that empowers peasants, pastoralists, fisherfolks, indigenous peoples, consumers and other groups, allowing their voice to inform policy making from community to national and international level. It lets these groups claim/achieve their right to food.

Judith Hitchman, Urgenci (France/UK) & Pedro Guzman, RENAF (Colombia)

The political dimension of agroecology gives practical expression to food sovereignty, placing small-scale food producers at the heart of policy processes and decisions that affect them. It seeks to meet multiple challenges from security of access to productive resources (land, water, seed), to food and nutrition security through climate resilience with sustainable long-term solutions that promote agroecological diversification and food sovereignty. Agroecology movements, that are commonly composed of grassroots food producers and consumer-led, are promoting a spreading of agroecology to other farmers and communities (horizontal scaling up or scaling out). Alongside scaling out, the political dimension requires a favourable public policy environment in which agroecological solutions can be multiplied (vertical scaling up).

Example 1: The benefits of a farmer-led transition to agroecology in the Philippines

MASIPAG (Magsasaka at Siyentipiko para sa Pag-unlad ng Agrikultura or Farmer-Scientist Partnership for Development) is a network of small-scale farmers, NGOs and scientists from the Philippines. The network covers over 35,000 farmers and works to support them as they transition to farmer-led sustainable agriculture and as they try to develop a socio-political and economic context in favour of sustainable family farming. While the organisation promotes agroecology, it does so within a farmer-led context that prioritises the knowledge and involvement of farmers including in breeding rice, the development of location specific farmer-led agroecological systems, the training and involvement of other farmers through farmer-to-farmer knowledge exchange and the development of marketing schemes based on participatory guarantee systems. Seed in the hands of farmers – and their knowledge of how to breed and improve varieties – is a way of reclaiming seed over this important common good and farmers’ answer to being lock-in to intellectual property on seed and the free, subsidized distribution of input-reliant seed. The MASIPAG farmers have developed a range of farming techniques that are adaptable to different agro-climatic conditions and are free of corporate control. The farmer-led breeding process helps ensure seed is well adapted and performs well. If disaster strikes, farmers in unaffected areas provide seed for affected farmers. To improve seed availability, most provincial organisations have a policy of seed reserves. Exploiting varieties of different resistances and tolerances – which is essential to the network’s climate resilience strategy – requires over 2,000 rice varieties from MASIPAG. Currently, MASIPAG has identified and bred 18 drought-tolerant, 12 flooding-tolerant, 20 saltwater-resistant and 24 pest-resistant rice varieties.

In 2009, a study based on interviews with 280 fully organic farmers, 280 converting to organic and 280 conventional farmers as reference group provided convincing evidence that the MASIPAG approach had improved food security and nutrition, health and the financial situation of farming families. Fully organic farmers had high on-farm diversity, producing on average a 50% bigger crop than conventional farmers, better soil fertility, less soil erosion, increased tolerance of crops to pests and diseases and better farm management skills. They ate a more diverse, nutritious and secure diet and their net incomes per hectare were one and a half times higher than those of conventional farmers. On average, they had a positive annual cash balance and were less indebted than conventional farmers, whose household budget was in deficit. Even farmers converting to organic had improved incomes and food security.

This demonstrates the effect of the political dimension when farmers and food producers work together to regain control over resources by involving all protagonists and farmer/scientist partnerships, which overcome unbalanced power relationships. This has a positive impact on other dimensions of agroecology, as is the case with the social, cultural economic and environmental dimensions.

Sources/further information

Bachmann, L., Cruzada, B., Wright, S. (2009). Food Security and Farmer Empowerment. A study of impacts of farmer-led sustainable agriculture in the Philippines.

Example 2: Creating national agroecology platforms to address political dialogue in Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali

In Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali, civil society has organized several consultations since 2016 to build a collective approach to addressing agroecology nationally. Several farmers’ organizations and local, national or international NGOs are interested in testing, implementing or promoting agroecology as a practice but also as a social movement. To develop a common vision and improve political dialogue with government, they decided to create national platforms that shared the same vision on agroecology.

In CCFD–Terre Solidaire’s programme on agroecological transition (PAIES), partners in three countries (Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger) were involved in creating and defining these platforms: the Plateforme national sur l’agroecologie paysanne (national platform for peasant agroecology – Mali), the Collectif Citoyen pour l’Agroécologie (people’s collective for agroecology – Burkina Faso) and the Plateforme Raya Karkara (Niger).

As regards the political dimension of agroecology, platforms have tried to include all constituencies (farmers, women groups (especially food processers), consumers and researchers) and are intending to set up a more local (regional) agroecological platforms. In their vision and planning, they all want to work on regaining control over land, water and seed.

These platforms are now actively promoting peasant-based seed systems (and also opposing cotton GMOs in Burkina Faso). In these three countries, national studies exist or are in progress on existing legal seed systems. Farmers’ organizations and researchers are being encouraged to meet and develop specific positions on peasant seed in order to propose new legislation that will include and protect peasant seed. In Burkina Faso, due to a West African coalition (COPAGEN) that produced a report on the effect of GMOs, a moratorium on GMO research was proposed to the national research institute.

CCFD–Terre Solidaire produced a review in late 2017 of these three organizations covering their origins, current activities and future initiatives. It took them some time to define a common vision on agroecology. Mali went a step further by focusing on peasant agroecology. The main political demands of these platforms include agroecology in national agriculture policies and their related implementation programmes. Some have already started specific advocacy such as an agroecology master in Niger or the creation of multi-stakeholder review process in Mali.

Sources/further information :

Mali :

– More about the national platform and its manifesto on agroecology (French)

– The seed system study in Mali (French): « Semences, normes et paysans: état des lieux du cadre normatif et institutionnel du système semencier et de la place des semences paysannes et des droits des agriculteurs au Mali »

Burkina Faso:

– Cotton Bt GMO peasant research (French): « Le coton BT et nous: la vérité de nos champs – synthèse d’une recherche paysanne sur les impacts socio-économiques du coton Bt au Burkina Faso »

Agroecological platforms review:

– In French: « Capitalisation du processus de structuration des plateformes agroecologiques au Mali, Niger et au Burkina Faso »

Conclusion

As highlighted in the introduction, the social, environmental and economic crisis we face calls for a profound change in the way our food systems are organised. Climate change makes it an imperative and adds a certain sense of urgency. This necessitates tackling all four dimensions of agroecology together. The separation into several dimensions helps us to understand the potential of agroecology more clearly, but it must be seen as a whole, as a holistic approach. Indeed, many farmers and peasants stress the holistic character of agroecology, as a way of living, something which gives sense to life. To them, it is not merely about providing a means of livelihood and a sustainable agro-ecosystem but of living in harmony with nature and other people. Equally, the potential impact of agroecology must not be limited to a single dimension.

Unfortunately, lack of clarity has been used by some to weaken the concept of agroecology: “suddenly agroecology is in fashion with everyone, from grassroots social movements to the FAO, governments, universities and corporations. But not all have the same idea of agroecology in mind. While mainstream institutions and corporations for years have marginalized and ridiculed agroecology, today they are trying to capture it. They want to take what is useful to them – the technical part – and use it to fine tune industrial agriculture, while conforming to the monoculture model and to the dominance of capital and corporations in structures of power”. This paper is our own attempt to clarify what agroecology means, what it looks like and show that, when taken as a whole, agroecology and its various principles can lead to tremendous positive effects in terms of human rights and the right to food. At the same time, it contributes to tackling the root causes of the issues our societies are currently facing and challenging existing power structures. This is why agroecology, as a movement, is key to us.

We are well aware that ultimately, many complimentary political actions, a transition process and a paradigm shift will be required for agroecology to deliver and its principles be applied jointly and progressively. We are also aware that the principles listed above might evolve, might need to be revised, might not be perfectly well phrased or not 100% in line with what agroecology looks like in practice. But we see this as a first step in a wider process that will eventually lead to an updating and further illustration of the current list of principles we identified.

Prof. Michel Pimbert, Coventry University (UK)

Next steps include building a “practical guide to using the principles” that would ideally serve as a basis for initiating dialogue between our organisations (on advocacy strategies and programmes and consistency between them) as well as within the broader agroecological movement. This therefore needs to be seen as a living document and an invitation to start a dialogue on what agroecology means and looks like.

Who We Are

This document has been developed by the CIDSE Task Force on agroecology and is the result of a collaboration and dialogue held over the past year.

The group consists of the following member organisations: Broederlijk Delen (Belgium), CAFOD (England and Wales), CCFD-Terre Solidaire (France), Entraide & Fraternité (Belgium), Focsiv (Italy), KOO/DKA (Austria), MISEREOR (Germany), SCIAF (Scotland) and Trócaire (Ireland).

CIDSE is an international family of Catholic social justice organisations working together with others to promote justice, harness the power of global solidarity and create transformational change to end poverty and inequalities.

Contact: François Delvaux, Climate & Agriculture and Food Sovereignty Officer, delvaux(at)cidse.org

Resources

CIDSE website: www.cidse.org

The Principles of Agroecology- Towards just, resilient and sustainable food systems, by CIDSE

Climate-Smart Agriculture: the Emperor’s new clothes? by CIDSE